Clinical Pathology Case Study: Feline infectious peritonitis in a cat

Background information

| Age: | 9 years |

| Sex: | Male |

| Species: | Feline |

| Breed: | Domestic longhair |

| History: | Sustained anorexia |

Clinical signs

- On ultrasound an abdominal effusion was present and the liver and spleen were enlarged.

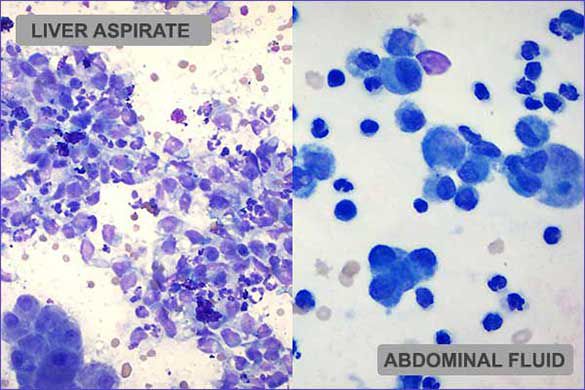

- Both, abdominal fluid and hepatic aspirates were submitted for cytology.

- The abdominal fluid was classified as an exudate, with a protein concentration of 63 g/L.

Cytologic description and interpretation

Abdominal fluid: The direct slide is moderately to highly cellular and cells are scattered individually and in loose collections. Macrophages and non-degenerate neutrophils predominate. Lymphocytes are present occasionally. The background has abundant protein-rich fluid and low numbers of erythrocytes.

Liver: The most diagnostic slide from the liver is highly cellular and of excellent quality. Hepatocytes have exfoliated in aggregates and sheets. Cells are generally uniform and have characteristic nuclear features.

Accumulations of blue/green granular material (lipofuscin) and green/brown material (bile) are visible within or between adjacent hepatocytes. Low numbers of hepatocytes have mild cytoplasmic vacuolation or rarefaction. Inflammatory cells are scattered in moderate to abundant numbers throughout the hepatocyte population. Large round cells (suspected to be macrophages) are most abundant and often form large sheets.

The cells have a moderate to abundant amount of light basophilic cytoplasm. The nucleus is generally oval but often has slightly uneven edges. Chromatin varies from loose/smooth to mildly stippled. Neutrophils are also present in moderate to abundant numbers. Lymphocytes and plasma cells are present rarely. The background consists of blood, cellular debris, purple fluid and collections of magenta material (lubricant).

Interpretation: Findings were consistent with an exudative abdominal effusion and marked pyogranulomatous inflammation in the spleen and liver. No etiologic agent was evident. However, the most likely cause for these findings was feline infectious peritonitis (FIP).

Further diagnostics

The abdominal fluid sample was submitted for feline coronavirus PCR with biotyping and was positive for the FIPV biotype. After euthanasia, tissue samples were sent for histopathology and findings were also supportive of FIP.

Discussion

Feline coronavirus (FCoV) is found worldwide and infection is reported to be highly prevalent1. Most often, the infection results in no clinical signs or mild enteric disease with infection limited to the gastrointestinal tract. However, up to 12 % of felines infected with FCoV may develop FIP2. FIP is a severe systemic pyogranulomatous disease that progresses quickly and is ultimately fatal1. It is a notoriously problematic disease to diagnose, and given the associated grave prognosis, many cats are euthanized with a presumptive FIP diagnosis. The difficulty in diagnosing FIP is a consequence of the vague/nonspecific clinical signs and high prevalence of FCoV infection in the feline population. There are two recognized biotypes of FCoV: feline enteric coronavirus (FECV) and feline infectious peritonitis virus (FIPV), which have very different clinical outcomes. The IDEXX FIP Virus RealPCR Test is able to differentiate between the benign (FEVC) biotype and fatal (FIPV) biotype. The FIP Virus RealPCR Test should be used as a confirmatory diagnostic test in patients with suggestive clinical and laboratory findings for FIP. In patients suspected of the wet form of FIP, the test can be performed on abdominal or thoracic effusions. For patients suspected to have the dry form of FIP, aspirates or biopsies of affected tissues can be submitted. Whole blood or fecal samples are not recommended for the test.

FIPV RealPCR Test provides a more definitive diagnosis of FIP without the traditional need for biopsy, histopathology and immunohistochemistry. As sample collection is generally less invasive for the FIPV RealPCR Test, the diagnosis of FIP can be made available to many more patients. This method allows veterinarians and their clients to be more confident they are making the best decisions for these pets and negates incurring additional costs for further diagnostics and ineffective treatments. Ultimately, this allows the owner to have higher quality interactions with their pets, during the patient's remaining time.

About the author

Heidi Peta DVM, MVSc, DACVP

Dr. Peta received her DVM in 2002 from the Western College of Veterinary Medicine (WCVM) at the University of Saskatchewan. She spent 1 year in small-animal private practice in Edmonton, Alberta, before returning to WCVM in 2003 to begin a 3-year residency in clinical pathology. Her time there was spent performing diagnostic duties, teaching veterinary students and completing a master’s project on GLDH, a liver enzyme in dogs. After the final year of her residency, Dr. Peta earned American College of Veterinary Pathologists (ACVP) board certification. She worked at a veterinary laboratory near Seattle before joining IDEXX Reference Laboratories in 2006.

Should you have any questions about this case or wish to discuss the diagnosis in greater detail, please do not hesitate to .

View clinical pathology case studies

NEW: Dermatophytosis in a dog, by Caroline Piché, DMV, IPSAV, MSc, Diplomate ACVP

Anaplasmosis in a dog, by Julie Webb, DVM, DACVP

Blastomycosis in a dog, by Julie Webb, DVM, DACVP

Cryptococcus in a dog, by Carrie Flint, DVM, DACVP

Cutaneous mycobacteriosis (Leprosy) in a cat, by Natalie Kowalewich, DVM, DACVP

Demodex in a dog, by Brittney Fierro, DVM, DACVP

Feline infectious peritonitis in a cat, by Heidi Peta DVM, MVSc, DACVP

Mammary fibroepithelial hyperplasia in a young cat, by Emmeline Tan, DVM, DVSc, DACVP

Microvascular dysplasia in a dog, by Cathy Monteith DVM, MVSc, DACVP

Severe hyperglobulinemia in a dog, by Sébastien Overvelde, DVM, MSc, DACVP

References:

- Sykes et al. Canine and Feline Infectious Diseases, 1st ed. St. Louis: Saunders Elsevier, c2014. Chapter 20, Feline Corona virus infection; p. 195-207.

- Addie D, Belák S, Boucraut-Baralon C, et al. Feline infectious peritonitis. ABCD guidelines on prevention and management. J Feline Med Surg. 2009;11(7):594–604.

All case studies were prompted by real submissions to IDEXX Canada pathologists at one of our reference laboratories.

To protect the confidentiality of our customer and clients, the background information in each case has been slightly modified.