Exposure to tick-borne diseases increases risk of developing CKD

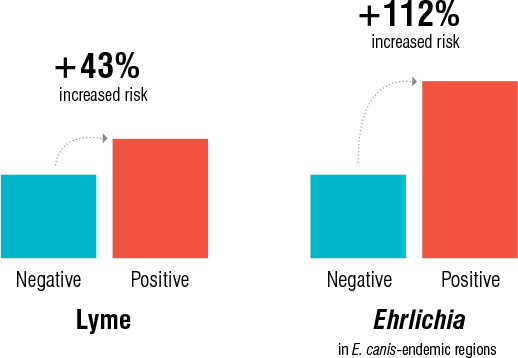

Two retrospective studies1,2 were performed to determine if exposure to tick-borne disease is associated with an increased risk of kidney disease. These studies identified an association between dogs with positive Lyme disease or Ehrlichia test results and an increased risk for chronic kidney disease (CKD) in endemic areas. Dogs with a positive Lyme disease antibody test result had a 43% increased risk of developing CKD, and dogs with a positive Ehrlichia antibody test result in Ehrlichia canis-endemic areas had a 112% increased risk of developing CKD (figure 1).

Risk of CKD

Figure 1. Risk of CKD relative to positive Lyme- or Ehrlichia-positive test results in dogs in endemic areas.

Introduction

Tick encounters are increasingly hard to avoid. These adaptable parasites are responsible for spreading a variety of diseases throughout the United States, and their range is increasing. To protect pets and people, we need to stay alert to the risks. That means regularly screening pets —including asymptomatic or seemingly healthy ones—to identify exposure to infected ticks. Remember that a single tick can transmit multiple infectious agents that can cause serious illness. The harmful impact that any given infection has on a pet’s health can sometimes be challenging to ascertain, particularly in asymptomatic pets.

Clinical presentation of Lyme disease and ehrlichiosis are inconsistent

For Lyme disease, controlled-infection studies have demonstrated that only a fraction of the dogs with joint capsule pathology show clinical signs of polyarthritis.3,4 Even fewer exposed dogs demonstrate severe kidney involvement manifested as acute progressive and often fatal protein-losing nephropathy that is classically recognized as Lyme nephritis.5 Therefore, simply relying on clinical signs of lethargy or shifting-limb lameness may not be sufficient to alert veterinarians to an underlying disease process affecting the joints, kidneys, or other body systems. Similarly, for ehrlichiosis, practitioners may rely on hematologic and biochemical abnormalities, such as thrombocytopenia and hyperglobulinemia, to indicate active infection in a seropositive dog. However, during the subclinical phase of ehrlichiosis, these abnormalities may be inconsistent or mild6 due to compensatory mechanisms.

Study design

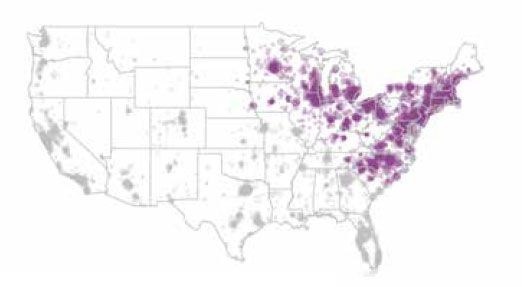

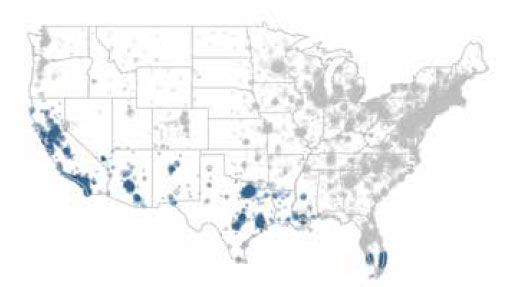

Two retrospective cohort studies were performed at IDEXX to determine if exposure to tick-borne disease is associated with an increased risk of kidney disease.1,2 For both studies, patient selection included dogs residing in the United States having a minimum of one SNAP 3Dx, SNAP 4Dx, or SNAP 4Dx Plus test result and at least one IDEXX SDMA Test result and one creatinine result. Urine specific gravity was also collected but not required. Data used in the study to diagnose kidney disease were collected from the IDEXX Reference Laboratories between July 13, 2015, and January 17, 2017, for the Lyme study and between July 13, 2015 and January 1, 2018, for the Ehrlichia study. Vector-borne disease data from this same cohort were then obtained from IDEXX Reference Laboratories and IDEXX SmartService Solutions databases to determine patient exposure to tick-borne disease between January 1, 2003, and January 1, 2017 (Lyme), and January 1, 2003, and January 1, 2018 (Ehrlichia). Patient populations were restricted to the geographies known for local transmission of Borrelia burgdorferi, the causative agent of Lyme disease (figure 2a), and Ehrlichia canis, a subspecies of Ehrlichia (figure 2b).

Purple dots represent Lyme disease-endemic areas.

Figure 2a. Lyme disease-endemic areas.

Blue dots represent E. canis-endemic areas

Figure 2b. E. canis-endemic areas

For both Lyme and Ehrlichia, patients exposed to infected ticks were defined as having a minimum of one positive vector-borne disease test result in their available history. Patients that were not exposed to infected ticks were defined as having only negative vector-borne disease results in their available history. Well-established chronic kidney disease (CKD) was defined as concurrent increased SDMA (> 14 μg/dL) and creatinine (> 1.5 mg/dL) for a minimum of 25 days with inappropriate urine specific gravity (USG <1.030) during that time. Additionally, neither SDMA nor creatinine levels could return to normal ranges in the available patient history. A statistical technique called propensity score matching was used to control for impacts of age, breed, and region on vector-borne disease exposure. So, every vector-bornedisease exposed dog was matched with four unexposed dogs with similar risk factors. Total number of patients included in each study were N = 322,145 for Lyme and N = 22,440 for E. canis. The study was designed to determine if there was an association between tick-borne disease and CKD. The design does not allow inference of a causal relationship, rather it indicates a statistically significant association between the two conditions.

Study limitations include that the data does not identify the following: (1) time of tick exposure, (2) time of onset of vector-borne disease, (3) clinical presentation, (4) treatment, or (5) patient outcome.

Results

The canine population for the Lyme data ranged in age from 1–25 years and included all genders and breeds (160 named breeds plus “other” comprising 34.4% of the population). The relative risk of CKD for patients exposed to ticks carrying B. burgdorferi within the defined Lyme disease region was found to be 1.43 with 95% confidence interval (CI) [1.27, 1.61], P < 0.0001, which means these dogs have a 43% increased risk of developing CKD. The canine population for the Ehrlichia data ranged in age from 0–25 years and included all genders and breeds (183 named breeds plus “other” comprising 32.1% of the population). The relative risk of CKD for patients exposed to ticks carrying Ehrlichia within E. canis-endemic areas was found to be 2.12 with 95% CI [1.35, 3.15], P = 0.0006, which means these dogs have a 112% increased risk of developing CKD. For each comparison that was performed, statistical significance was defined by a P value of < 0.05

Discussion

Dogs with antibodies to the C6 peptide of B. burgdorferi had a 43% increased risk of developing CKD, and dogs with Ehrlichia antibodies in E. canis-endemic areas had a 112% increased risk of developing CKD. Both results were statistically significant and clinically relevant, indicating that regular monitoring of these seropositive patients is medically necessary. Although the design of this retrospective study does not allow for determination of a causal relationship, the findings reveal a statistically significant association between positive Lyme disease or Ehrlichia test results in endemic areas and an increased risk for CKD. It should be noted that although E. canis is found in higher frequency in certain geographic regions of the U.S., dogs infected with E. canis can be found throughout the U.S. E. canis has been identified via polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing in specimens submitted to IDEXX Reference Laboratories from 42 of 50 states since 2011. Screening patients exposed to infected ticks with a chemistry panel that includes the IDEXX SDMA Test, which detects a highly sensitive and specific biomarker of kidney function, can help identify early kidney disease that may be a complication of vectorborne diseases, such as Lyme disease and ehrlichiosis.

Symptomatic dogs that have been exposed to ticks infected with B. burgdorferi or Ehrlichia have an increased risk of multisystemic disease.3,7 This study supports that dogs who test positive for Lyme disease or Ehrlichia in endemic areas are associated with a statistically significant increased risk of developing CKD. Consequently, patients of any age that test positive for Lyme disease or Ehrlichia should be considered for comprehensive evaluation. In addition to vector-borne disease screening, these patients should receive a physical examination, a complete blood count (CBC), a complete chemistry panel with the IDEXX SDMA Test, and a urinalysis with sediment to monitor for multisystemic disease.

Since patients with vector-borne disease may have other systemic issues or chronic lameness resulting in decreased muscle mass, creatinine concentrations may no longer be a good estimate of renal function. Finding an increased SDMA in a dog with verified tick exposure indicates an immediate course of action to investigate, manage, and monitor possible kidney disease with guidance from the IDEXX SDMA Test diagnostic algorithm.* Incorporating SDMA testing into the diagnostic profile will help to identify kidney changes that might otherwise be missed since SDMA is a more reliable biomarker than creatinine. In the patients that are seropositive for B. burgdorferi, Lyme quantitative C6 antibody testing (Lyme Quant C6 Test) is also recommended.

Conclusion

In summary, this study identified an association between dogs with positive Lyme disease or Ehrlichia test results in endemic areas and an increased risk for CKD. Dogs with a positive Lyme disease antibody test result had a 43% increased risk of developing CKD, and dogs with a positive Ehrlichia antibody test result in E. canis-endemic areas had a 112% increased risk of developing CKD.

Screening patients exposed to ticks with a chemistry panel that includes the IDEXX SDMA Test can help identify early kidney disease that may be a complication of vector-borne diseases, such as Lyme disease and ehrlichiosis. In addition to vector-borne disease screening, these patients should receive a physical examination, a complete blood count (CBC), a complete chemistry panel with the IDEXX SDMA Test, and a urinalysis with sediment to monitor for multisystemic disease.

Identify exposure with the SNAP 4Dx Plus Test

The most trusted pet-side comprehensive vector-borne disease screening test

References

- Drake C, Ogeer JS, Beall MJ, et al. Investigation of the association between Lyme seroreactivity and chronic kidney disease in dogs [ACVIM Abstract ID08]. J Vet Intern Med. 2018;32(6):2264.

- Burton W, Drake C, Ogeer J, et al. Association Between Exposure to Ehrlichia spp. and Risk of Developing Chronic Kidney Disease in Dogs. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 2020; 56:159–164.

- Summers BA, Straubinger AF, Jacobson RH, Chang YF, Appel MJ, Straubinger RK. Histopathological studies of experimental Lyme disease in the dog. J Comp Pathol. 2005;133(1):1–13.

- Wagner B, Johnson J, Garcia-Tapia D, et al. Comparison of effectiveness of cefovecin, doxycycline, and amoxicillin for the treatment of experimentally induced early Lyme borreliosis in dogs. BMC Vet Res. 2015;11:163.

- Littman MP. Lyme nephritis. J Vet Emerg Crit Care. 2013;23(2):163–173.

- Harrus S, Waner T. Diagnosis of canine monocytotropic ehrlichiosis (Ehrlichia canis): an overview. Vet J. 2011;187(3):292–296.

- Little SE. Ehrlichiosis and anaplasmosis in dogs and cats. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2010;40(6):1121–1140.

*The IDEXX SDMA diagnostic algorithm is available at idexx.ca/AlgorithmSDMA